Le necessità del dente sono le necessità biomeccaniche del dente al fine di svolgere la propria funzione in maniera predicibile nel tempo; rappresenta quindi la minore asportazione di sostanza dentale compatibile con le necessità dell'operatore e le necessità restaurative.

|

Valore rispetto al dente

|

tipo di tessuto

|

|

alto

|

PCD (dentina pericervicale)

dentina sottominata

giunzione dentina -dentina secondaria

pareti assiali

smalto cervicale nei denti giovani

|

|

medio

|

smalto coronale

|

|

basso

|

dentina secondaria

|

|

nessun vantaggio se non danno

|

dentina terziaria

smalto sottominato

polpa infiammata

giunzione cementodentinale in pazienti parodontopatici e/o con cariocettività radicolare

|

La ricerca in tal senso è inecquivocabile: la ritenzione a lungo termine di un dente e la sua resistenza alla frattura sono direttamente prorporzionali alla dentina residua.

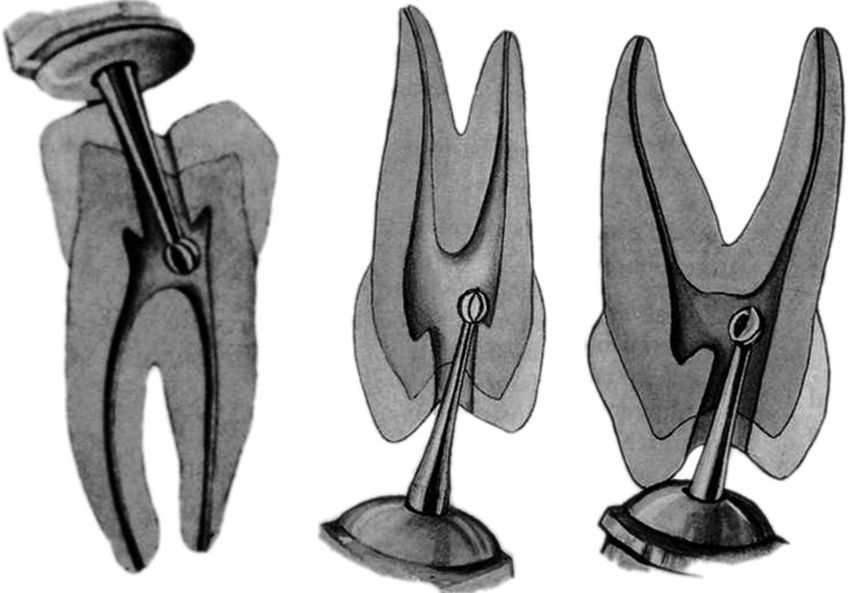

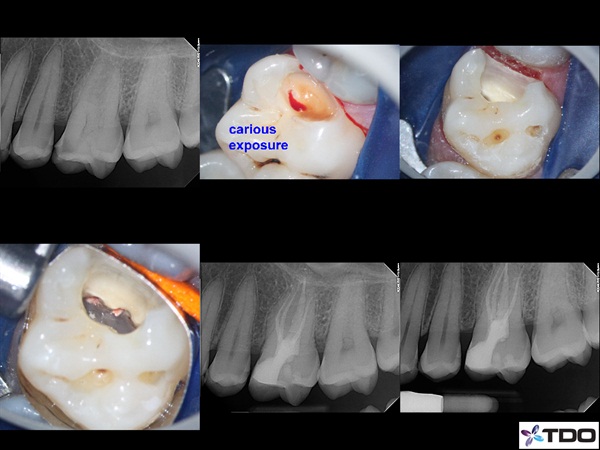

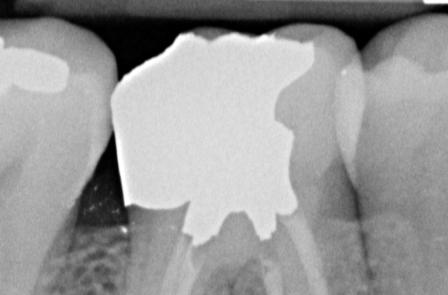

Queste immagini, così frequentemente mostrate nelle scuole dentali e nei libri di testo e nei corsi, sono detatte da modelli mentali basati sulla carie occlusale nei bambini. Se la camera pulpare è sufficientemente larga. Allora una fresa rotonda può davvero sprofondare nella camera pulpare, come mostrato nella fig.8, con una fresa #6 a palla. Ma è evidentemente un modello basato sulla sensazione tattile dello sprofondamento, modello valido solo in una piccola percentuale di casi e che può creare seri danni.

fig.8

fig.8

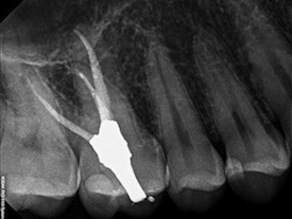

fig. 9

fig. 9

I risultati a lungo termine, 20-40 anni, dei denti trattati endodonticamente presentano due caratteristiche fondamentali:

– hanno poco a che fare con ciò che tradizionalmente noi chiamiamo qualità del trattamento endodontico, ovverossia endodonzie di "bassa qualità tecnica" hanno percentuali di successo endodontico (cioè riguardo alla patologia periapicale) più o meno simili alle endodonzia di "elevata qualità tecnica"

– la conservazione della dentina prevale di gran lunga su quello che noi chiamiamo oggi qualità di un trattamento endodontico riguardo al successo endo-restaurativo

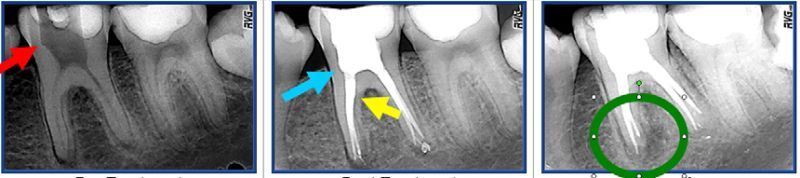

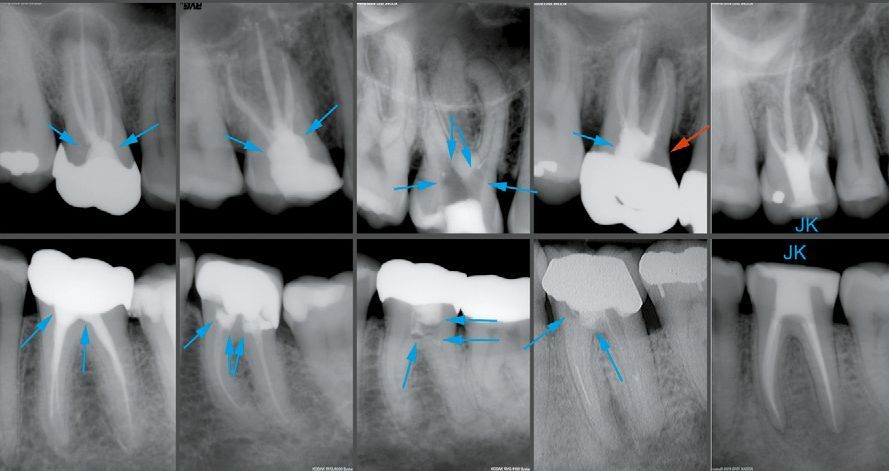

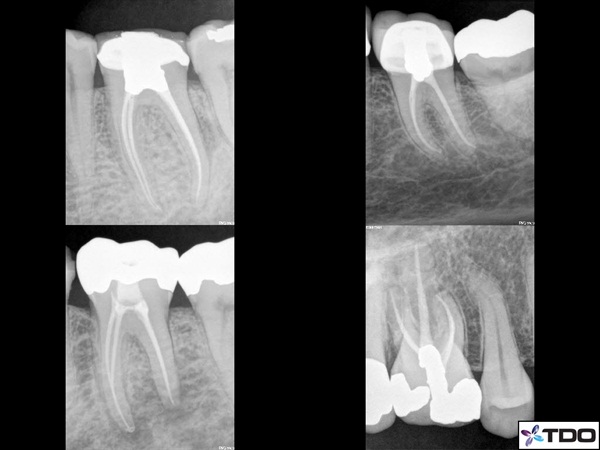

Nell'immagine sottostante le frecce blu indicano i "gouges" (gli eccessi di apertura). Le frecce rosse le perforazioni. Le ultime due Rx sup. e inf. rappresentano ciò che è ottenibile e ciò che è anche auspicabile per un successo a lungo termine di un dente trattato endodonticamente.

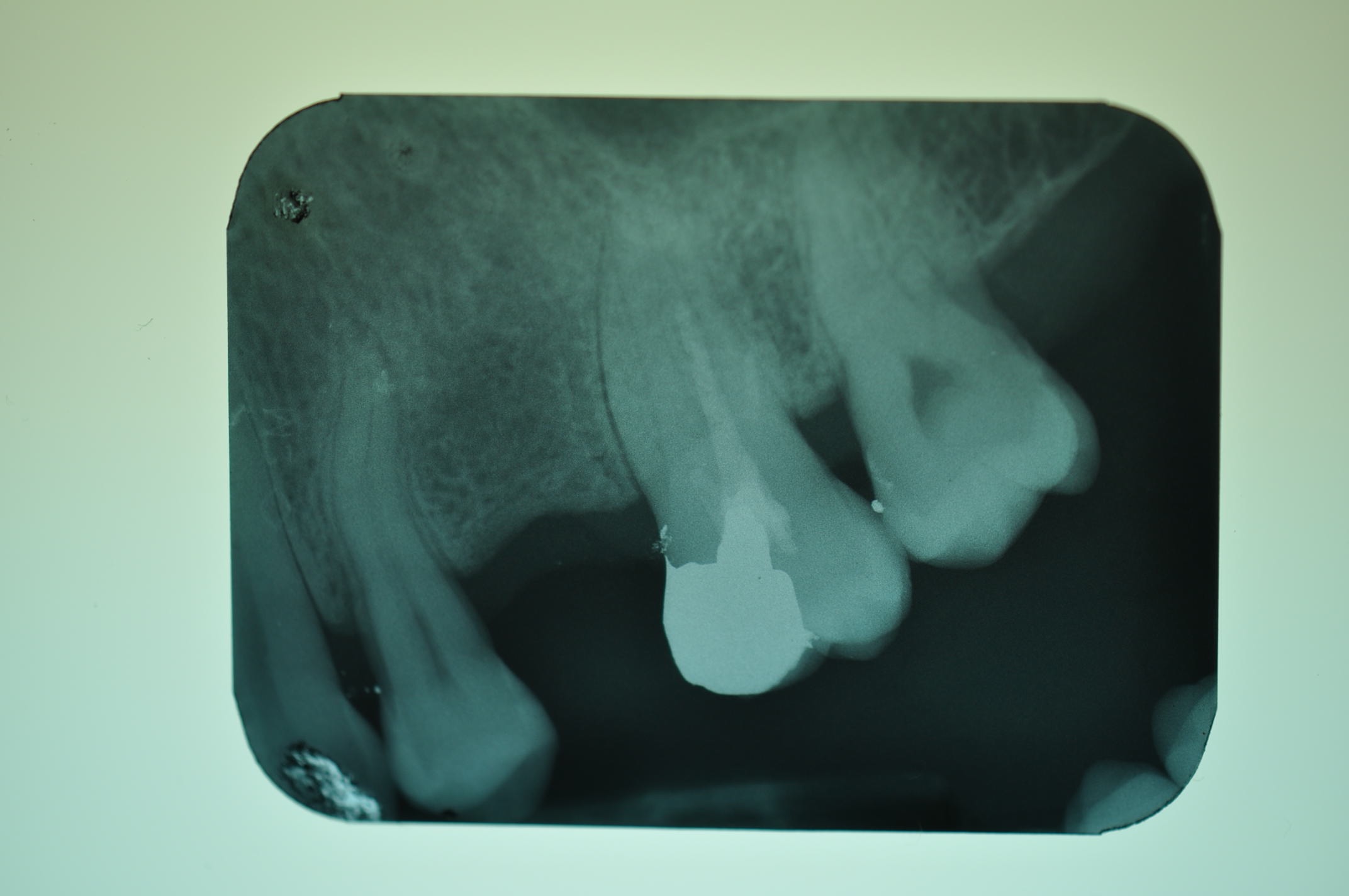

Ecco una serie di cavità di accesso errate, cosiddette "gouged": esempi di cosa non dobbiamo mai fare!!

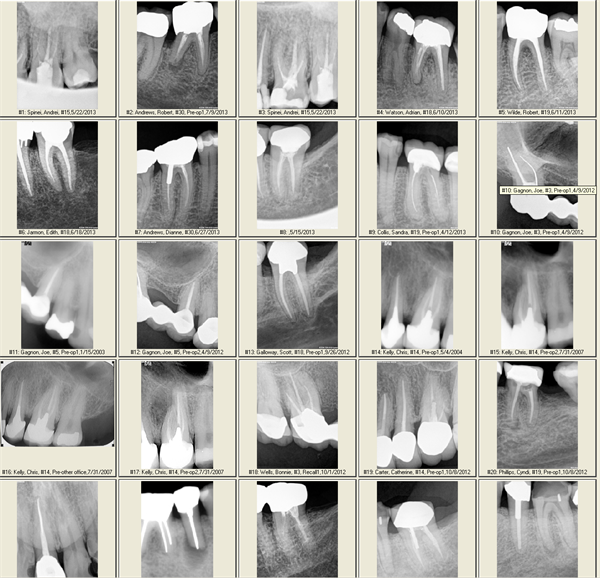

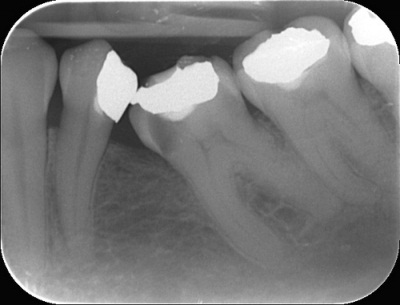

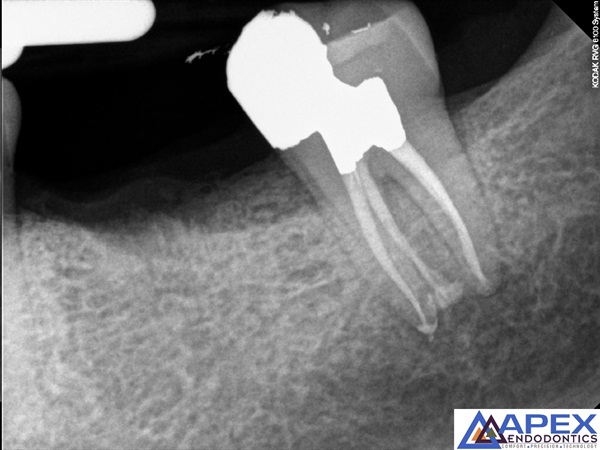

Ecco invece una serie di casi di come vanno eseguite delle corrette cavità di accesso:

dott. Rob Corr

Dr. Jeff Pafford

Le 3 regole per non fare STRIKE!

Clark and Khademi hanno osservato che, nei casi trattati endodonticamente con follow-up a 20 e 40 anni, questi denti erano violati sempre in meno di 3 modi: cioè i casi con una tale longevità hanno non più dei due dei seguenti danni iatrogeni:

– eccessiva riduzione assiale

– accesso endodontico "gouged", cioè generoso e mutilante

– conicità endodontica ampia e arbitrariamente rotonda

Tutte queste 3 violazioni sono insulti irreversibili alla dentina perircervicale con conseguente compromissione della prognosi dell'elemento dentario in questione.

Quando ci accingiamo a valutare la possibilità di un ritrattamento la prima cosa da fare è valutare in quanti modi il dente è già stato violato. Qualora sia stato violato in più di 2 modi, la prognosi è sfavorevole e dovremmo considerare l'estrazione dello stesso e l'implantologia.

Bibliografia

REFERENCES

1. Tay FR, Pashley DH. Monoblocks in root canals: a hypothetical or a tangible goal. J Endod 2007;33(4):391–8.

2. Wahl MJ, Schmitt MM, Overton DA, et al. Prevalence of cusp fractures in teeth restored with amalgam and with resin-based composite. J Am Dent Assoc2004;135:1127–32.

3. Schwartz RS, Robbins JW. Post placement and restoration of endodontically treated teeth: a literature review. J Endod 2004;30(5):289–301.

4. Lirtchirakarn V. Patterns of vertical root fractures: factors affecting stress distribution in the root canal. J Endod 2003;29:523–8.

5. Tamse A. An evaluation of endodontically treated vertically fractured teeth. J Endod 1999;25:506–8.

6. Miles B. Sales data. New Jersey: SS White Bur Inc; 2008.

7. Tan PL, Aquilino SA, Gratton DG, et al. In vitro fracture resistance of endodontically treated central incisors with varying ferrule heights and configurations. J Prosthet Dent 2005;93(4):331–6.

8. Sahafi A, Peutzfeldt A, Ravnholt G, et al. Resistance to cyclic loading of teeth restored with posts. Clin Oral Investig 2005;9(2):84–90.

9. Kutesa-Mutebi A, Osman YI. Effect of the ferrule on fracture resistance of teeth restored with prefabricated posts and composite cores. Afr Health Sci 2004; 4(2):131–5.

10. Akkayan B. An in vitro study evaluating the effect of ferrule length on fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth restored with fiber-reinforced and zirconia dowel systems. J Prosthet Dent 2004;92(2):155–62.

11. Goto Y, Nicholls JI, Phillips KM, et al. Fatigue resistance of endodontically treated teeth restored with three dowel-and-core systems. J Prosthet Dent 2005;93(1): 45–50.

12. Ng CC, al-Bayat MI, Dumbrigue HB, et al. Effect of no ferrule on failure of teeth restored with bonded posts and cores. Gen Dent 2004;52(2):143–6.

13. Smidt A, Venezia E. The use of an existing cast post and core as an anchor for extrusive movement. Int J Prosthodont 2003;16(3):225–8.

14. Pierrisnard L, Bohin F, Renault P, et al. Corono-radicular reconstruction of pulpless teeth: a mechanical study using finite element analysis. J Prosthet Dent

2002;88(4):442–8.

15. Stankiewicz NR, Wilson PR. The ferrule effect: a literature review. Int Endod J 2002;35(7):575–81. Review.

16. Hsu YB, Nicholls JI, Phillips KM, et al. Effect of core bonding on fatigue failure of compromised teeth. Int J Prosthodont 2002;15(2):175–8.

17. Lenchner NH. Considering the ‘‘ferrule effect’’. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2001; 13(2):102.

18. al-Hazaimeh N, Gutteridge DL. An in vitro study into the effect of the ferrule preparation on the fracture resistance of crowned teeth incorporating prefabricated post and composite core restorations. Int Endod J 2001;34(1):40–6.

19. GegauffAG. Effect of crown lengthening and ferrule placement on static load failure of cemented cast post-cores and crowns. J Prosthet Dent 2000;84(2):169–79.

20. Morgano SM, Brackett SE. Foundation restorations in fixed prosthodontics: current knowledge and future needs [review]. J Prosthet Dent 1999;82(6):643–57.

21. Hunter AJ, Hunter AR. The treatment of endodontically treated teeth. Curr Opin Dent 1991;1(2):199–205. Review.

22. Loney RW, Kotowicz WE, McDowell GC. Three-dimensional photoelastic stress analysis of the ferrule effect in cast post and cores. J Prosthet Dent 1990;63(5): 506–12.

23. Jorgensen KD. The relationship between retention and convergence angle in cemented veneer crowns. Acta Odontol Scand 1955;13:35–40.

24. Wilson AH, Chan DC. The relationship between preparation convergence and retention of extracoronal retainers. J Prosthodont 1994;3:74–8.

25. Smith CT, Gary JJ, Conkin JE, et al. Effective taper criterion for the full veneer crown preparation in preclinical prosthondontics. J Prosthodont 1999;8:196–200.

26. Noonan JE Jr, Goldfogel MH. Convergence of the axial walls of full veneer crown preparations in a dental school environment. J Prosthet Dent 1991;66:706–8.

27. Ohm E, Silness J. The convergence angle in teeth prepared for artificial crowns. J Oral Rehabil 1978;5:371–5.

28. Annerstedt A, Engstrom U, Hansson A, et al. Axial wall convergence of full veneer crown preparations. Documented for dental students and general practitioners. Acta Odontal Scand 1996;54:109–12.

29. Lempoel PJ, Snoek PA, van’t Hof M, et al. [The convergence angel of crown preparations with clinically satisfactory retention]. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 1993;100: 336–8 [in Dutch].

30. Mou SH, Chai T, Wang JS, et al. Influence of different convergence angles and tooth preparation heights on the internal adaptation of Cerec crowns. J Prosthet Dent 2002;87:248–55.

31. Dodge WW, Weed RM, Baez RJ, et al. The effect of convergence angle on retention and resistance form. Quintessence Int 1985;16:191–4.

32. Shillingburg HT, Hobo S, Whitset LD, et al. Fundamentals of fixed prosthodontics. 3rd edition. Chicago: Quintessence; 1997.

33. Wiskott HW, Nicholls JI, Belser UC. The relationship between abutment taper and resistance of cemented crowns to dynamic loading. Int J Prosthodont 1996;9:

117–39.

34. Trier AC, Parker MH, Cameron SM, et al. Evaluation of resistance form of dislodged crowns and retainers. J Prosthet Dent 1998;80:405–9.

35. Maxwell AW, Blank LW, Pelleu GB Jr. Effect of crown preparation height on the retention and resistance of gold castings. Gen Dent 1990;38:200–2.

36. Park MH, Calverley MJ, Gardner FM, et al. New guidelines for preparation taper. J Prosthodont 1993;2:61–6.

37. Woolsey GD, Matich JA. The effect of axial grooves on the resistance form of cast restorations. J Am Dent Assoc 1978;97:978–80.